|

|

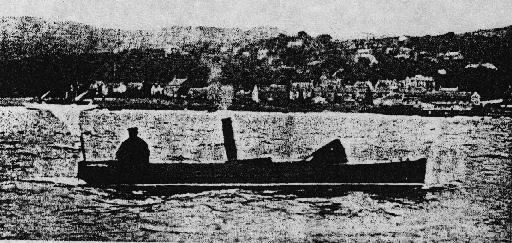

A Kelvin K2 (like No. 19194) but

with an electric start. |

|

|

A Kelvin K2 (like No. 19194) but

with an electric start. |

Having shared a boat with an elderly Kelvin for 12 years now, I know some of the ingredients of this Legend.

Ours (No. 19194) is a K2 - the two cylinder 44 hp slow running diesel, half brother of the K4 (88 hp) which has four cylinders, big brother of the K1 (22 hp one cylinder) and also related directly to the K3 (66 hp) and K6 (132 hp).

This engine was built in 1936 and was installed in Rolling Wave on November 17, 1936, replacing the smaller petrol/paraffin Kelvin which had been installed in 1929, when Rolling Wave herself was built.

A letter to Glasgow, quoting the engine number, produced a copy of the original individual engine specification, including tolerances by actual measurement, slow speed and full speed revs. on test (165-880), magneto number and fuel pump number, plus a list of irregularities and a copy of the engineer's report of August 12, 1938, when the Guarantee Overhaul was made. I was interested to see that the skipper reported a noise in the timing case: "...we started up and there was a noise like slackness in the gears, so we removed the flywheel and opened up the timing wheel case . . ." There was a little more lash than usual, but, trying new wheels effected no improvement.

Having satisfied ourselves that we could not improve matters, and that there was no danger, we closed up the timing case and put on the flywheel again."

This is of absorbing interest to me, because in 1971, 33 years later, there is still a noise like slackness in the gears. The main bearings are due for replacement, an operation which involves removing the flywheel, and thus providing an opportunity to open the timing case and examine the gears.

The thought of removing the flywheel sends shivers up my spine, because it is 31 1/4 in. diameter and must weigh a quarter of a ton. However, it can be taken off without disturbing the rest of the engine. If Messrs. McCulloch and Philips, the engineers who did the Guarantee Overhaul, were able to whip it off and on so casually in one working day in 1938, maybe Harper and his six friends, equipped with blocks, tackle, chains and jacks, may be able to emulate them over an entire winter, and have another look at the timing gears.

Part of the attraction of a Kelvin is that a rank mechanical idiot, like myself, armed with tools, handbook, and spares book can tackle most jobs. They are simple engines, designed to run for extended periods without much attention, and to be kept in good order by fishermen who have limited engineering experience. Any experienced mechanic finds them very straightforward to maintain, even if he comes to them completely new.

One of the unusual features of the K series of diesels is their extremely rare system of petrol starting. When the decompressed engine is pulled over compression, which any unusually strong man can do easily, an impulse magneto produces a spark in the plugs screwed into the petrol combustion chambers mounted on top of each cylinder. The explosion is directed into the diesel combustion chamber and drives the piston down. More petrol is drawn from a primitive carburettor, and the engine is running on petrol until you pull the decompression lever over, shutting off the petrol combustion chamber, and whacking up the compression ratio so that the engine runs on diesel from the injectors, all perfectly conventional and normal. The first firing stroke on diesel makes you think someone is attacking the engine with a sledgehammer.

A friend of mine dines out on his impersonations,

with sound effects, of Harper starting No. 19194.

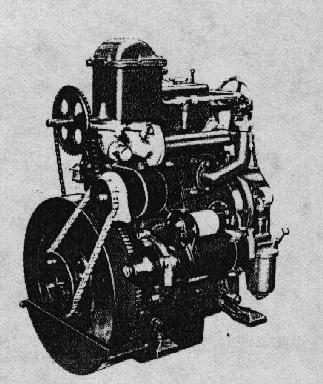

| One of today's Kelvins, the P2. It produces 10hp and has a stroke of 4in. The old K2 gave 44 hp and had a 9 in. stroke |  |

Once they are running, Kelvins go on forever, despite minor or major setbacks of the kind which stop other engines dead in their tracks.

We once brought Rolling Wave back to Shepperton from the Isle-of-Wight, under power, noticing a very smoky exhaust and a certain loss of power along the way. Investigation at leisure showed that when re-timing after replacing the coupling which drives the fuel pump a certain mechanical idiot, me, had re-timed the engine exactly 180 degrees out. I would have thought it impossible for an engine to run like this!

We have also had No. 19194 running backwards, which is quite alarming; firing in the crankcase, also alarming; and "running away", due to a governor drain valve being knocked open. He appears to bear us no malice for these indignities, all of which were my fault of course.

However, he himself once blew a plug clean out of the socket on top of the petrol combustion chamber, which was very frightening indeed.

I started him on petrol once with a petrol priming cock open, which resulted in petrol being blown out of the cock and igniting about two feet away from the cylinder head. This too was quite an experience.

Perhaps one can learn from these

events. Are they the kind of things which happen on boats with 100 per

cent petrol engines, and result in major explosions due to the presence

of petrol vapour?

The history of Kelvins is interesting. In 1904 Mr. Bergius gave his name to the Bergius Car & Engine Company, and by 1907 had actually produced 15 petrol driven cars. In 1906 a 23 ft. launch, called Kelvin, was fitted with a 12 hp four cylinder engine, an experiment so successful that the production of cars was later abandoned. An advertisement appeared in the July 19, 1906 issue of Motor Boat, announcing that Mr. Bergius's company was proposing to start building marine engines, named after the launch in which the experimental installation was made.

In 1907 a Cambeltown fishing boat, named The Brothers, had a 7 hp Kelvin engine installed. Many others followed, because at this time large numbers of small inshore fishing boats, working under sail 2nd oars alone, were laid up as unprofitable. Reliable engines completely changed the picture, because they could now work even though the winds were unfavourable.

|

|

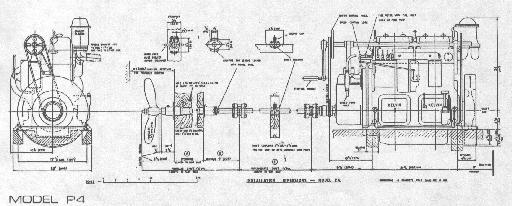

"A neat Kelvin Job". |

No launches were produced after 1939, as a result of the non availability of suitable wood after the end of the war.

The Company's name was changed in 1908 to the Bergius Launch & Engine Company, and in 1909 it moved to its present location, Dobbies Loan, Glasgow.

As Kelvins themselves say, many model K engines have suffered breakdowns because the owner, taking advantage of the small amount of attention they required, paid little heed to the maintenance instructions and expected the engine to perform naturally under ridiculous circumstances. To this, the author pleads guilty.

The J range, to the same basic design, followed the K, and there must be many yachtsmen who have experience of one or the other of these engines. The reason of course is that they do seem to last for ever.

K4's were standard equipment in Admiralty 61 ft. MFV's in the 1939 War.

The company has had a chequered career since the War, changing hands more than once, itself taking over Gleniffers in 1963, and is now the Kelvin Marine Division of English Electric Diesels Ltd, combining eight well known names in one group.

However, at the Boat Show the stand still appears to be manned by the same soft spoken Scots engineers, and although the range now extends from a 12 hp single cylinder air cooled engine to a 667 hp monster with 12 cylinders, turbo-supercharged and after cooled, to me Kelvins are still Kelvins, and it is a lucky yachtsman who owns one.

They are utterly reliable, access

is good and pretty well all maintenance can be done in situ; their slow

running means less wear and long life, and the fact that they are designed

as marine engines means that they are inherently right for the job they

have to do. However, in order to achieve one virtue, sometimes another

has to be sacrificed, and Kelvins are large, heavy, and expensive to buy.

Not all yachtsmen are prepared to write off their investment over

the many thousands of trouble free hours which these engines give, and

not all yachts have a large enough engine compartment to house one.